MCP: Tracing damage pathways

in diabetic kidney disease

Diabetic kidney disease is the most common cause of kidney failure and can occur as a complication of both Type I and Type II diabetes. In a paper published in the journal of Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, researchers at the University of Toronto and the Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques in Spain report a link between the proteomic changes caused by high levels of male sex hormones and impaired energy metabolism in diabetic kidney disease.

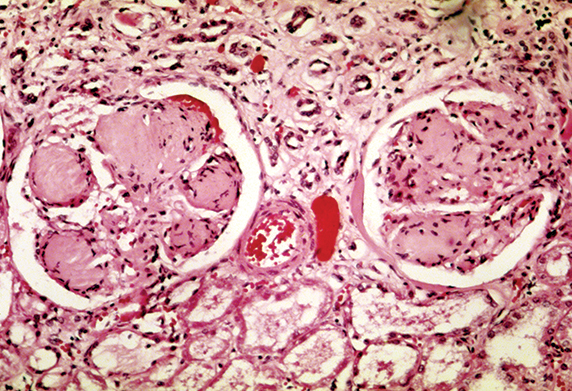

Patients with diabetic kidney disease can have kidneys with scarred glomeruli.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

“It’s been reported in previous clinical studies that male sex hormones predispose (patients) to many kidney diseases and lead to a more rapid progression and increased severity of kidney disease,” says Sergi Clotet, the first author on the paper and a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Ana Konvalinka at the University of Toronto. “Our findings proposed this novel link between male sex (hormones), energy metabolism and oxidative stress in the kidneys of diabetic animals, which are indicators of mitochondrial damage.”

Diabetic kidney disease causes the clustered kidney capillaries, known as glomeruli, to leak high levels of proteins, such as albumin, into urine. The leakage eventually leads to anemia, chemical imbalance in the bloodstream and overall decline in kidney function. The disease can be stemmed if caught early on but may be exacerbated in men by elevated androgens.

Clotet and colleagues used a variation of the SILAC technique for their study. In traditional SILAC, which stands for stable-isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture, the amino acids in cells are labeled with nonradioactive isotopes and quantified by mass spectrometry.

The SILAC variant, known as “spike-in,” enabled the investigators to bypass difficulties involved with labeling the primary proximal tubular cells, which don’t grow well in SILAC media, by labeling only transformed proximal tubular cells. The labeled transformed cell lysates then were combined with the unlabeled and stimulated primary cell lysates.

The investigators stimulated primary cells with 100 nanomolar doses of a sex hormone, either estradiol or dihydrotestosterone, and subjected them to mass spectrometry to identify the changes in metabolic regulation caused by each hormone.

After performing subsequent bioinformatics analyses, the researchers noticed that energy metabolism was impaired in the cells exposed to dihydrotestosterone. They validated their results by examining the expression of key enzymes involved in metabolism in kidneys of male and female normal and diabetic animals. The researchers then performed an enrichment analysis of their own data and a publicly available gene-expression data set generated from kidneys of patients with diabetes. With the analysis, the researchers were able to group and visualize significant functional categories. They found that oxidative stress was elevated significantly in the testosterone-treated samples from their dataset as well as in the kidneys of diabetic patients.

The researchers then decided to analyze oxidative stress levels and the sex differences in their animal groups, finding that the stress levels were increased in males of both normal and diabetic animals. “It’s a result that suggests that male sex is associated with more severe kidney disease,” says Clotet.

Clotet and colleagues intend to collect kidney biopsies from diabetic and nondiabetic male and female donors to validate their findings further as well as to look for biomarkers that could indicate early onset of diabetic kidney disease. “That could be a noninvasive way to predict sex-specific progression of diabetic and nondiabetic kidney diseases,” says Clotet. “At the end of the day, we want to explore more personalized treatments for kidney disease.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.