Taking stock

Recently, Bruce Alberts and co-authors concluded that biomedical research in the U.S. has become an “ unsustainable hypercompetitive system that is discouraging even the most outstanding prospective students from entering our profession.” They noted that we are producing about 8,000 Ph.D.s per year and only about 20 percent of recent Ph.D.s obtain academic positions. As they and others point out, this is a complex problem affecting the long-term competitiveness of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise, and they make a number of specific recommendations.

The author participates in a demonstration on May 5, 1971, in Washington, D.C. He recalls: “This photo was taken at about noon on the first day of the demonstration on M Street. This was a show of force by then-President Nixon. These were National Guard troops. I was reminding them that this was just a demonstration and to keep their guns in their pockets. Remember that this was just a little over a year since the student war protestor killings by National Guard troops at Kent State University. Memories were still vivid.“ Courtesy of Washington Star

The author participates in a demonstration on May 5, 1971, in Washington, D.C. He recalls: “This photo was taken at about noon on the first day of the demonstration on M Street. This was a show of force by then-President Nixon. These were National Guard troops. I was reminding them that this was just a demonstration and to keep their guns in their pockets. Remember that this was just a little over a year since the student war protestor killings by National Guard troops at Kent State University. Memories were still vivid.“ Courtesy of Washington Star

For those who are graduate students or postdoctoral fellows, these observations are sobering. So the question is where one goes from here. The answer is personal and not easy to come to, as the pressure to continue on is great and few graduate or postdoctoral programs are set up to help young scientists explore alternatives.

What I describe here is my odyssey through graduate school. It’s a product of the times, the 1960s and ’70s, and not unlike many others from that period. It’s certainly not meant as a model except in one respect: From time to time, during the early phases of your training (or life), it’s good to take a break.

Measured in fish

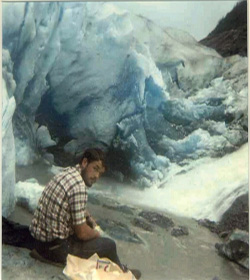

While hitchhiking south from Fairbanks, Alaska, the author had lunch with another traveler on an ice bridge on the edge of Mendenhall Glacier, just outside Juneau. “A moment later, the bottom of the bridge fell out, leaving the top and us. Otherwise, I’d still be there somewhere,” he recalled. “We scrambled off immediately. Sitting ducks. Episode 99 in surviving youth.”Image courtesy of Hensley

While hitchhiking south from Fairbanks, Alaska, the author had lunch with another traveler on an ice bridge on the edge of Mendenhall Glacier, just outside Juneau. “A moment later, the bottom of the bridge fell out, leaving the top and us. Otherwise, I’d still be there somewhere,” he recalled. “We scrambled off immediately. Sitting ducks. Episode 99 in surviving youth.”Image courtesy of Hensley

After undergrad, I took off the summer and did commercial salmon fishing in Alaska. I moved from a world where everything was measured in grades and papers (the University of California, Santa Barbara) to one where everything was measured in fish (Egegik, Alaska).

The coolest guy in town caught the most fish, the second coolest guy caught the second most fish, and so forth. (There was a scale factor for the size of the engine in your boat, but that just made the math more complicated.) At the end of the summer, I hitchhiked from Fairbanks, Alaska to San Francisco. That took about a week and provided stories upon stories. That was my first break from my trajectory since childhood. And it set an internal precedent, though I didn’t appreciate that at the time.

In the middle of my graduate career at Cornell University, I woke up and realized that I was there by choice as much as by lack of choice. I had just kept taking the next step. I was pretty unhappy but couldn’t tell anyone why, especially me. So I just stopped going into the lab.

Those were relaxed times, and my boss, Stuart Edelstein, was forgiving. Not sure that would work now. I went to live with my friends on a farm (hippies — you know the story) and milked cows and cut hay. Then I hitched from New York to California and back and all through eastern Canada (maybe 20,000 miles). The best of times. Great for recharging your humanity batteries.

Then one day I woke up again and doing calculations seemed like lots of fun, so back I went (and, importantly, I was allowed to). So that was a mini (but now slightly more conscious) internal sabbatical.

The tools of democracy

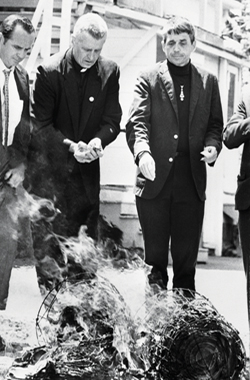

Philip Berrigan (left) and his brother, Daniel Berrigan, both Roman Catholic priests, watch two baskets of draft board records burn on May 17, 1968, after the records were removed from the Cantonsville, Md., draft board office. The Berrigans were arrested along with the seven other participants, including three other priests. Dan Berrigan was a mentor to the author: “He spoke in poetry and of the moral alternative to war.”Image courtesy of Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

Philip Berrigan (left) and his brother, Daniel Berrigan, both Roman Catholic priests, watch two baskets of draft board records burn on May 17, 1968, after the records were removed from the Cantonsville, Md., draft board office. The Berrigans were arrested along with the seven other participants, including three other priests. Dan Berrigan was a mentor to the author: “He spoke in poetry and of the moral alternative to war.”Image courtesy of Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

But the break wasn’t quite as clean as that, really. We were in the middle of the Vietnam War, and my draft number was 34. In 1969, we had a conscripted (drafted) military, in contrast with the volunteer military of today. These numbers were determined by lottery. If you had a low number, you were off to Vietnam; if you had a high number, you were not. Mine was not high, and I was classified 1A, or fit for service. My conscientious objector petition had been turned down, so Canada was on my horizon. Remember the line from Samuel Johnson about facing the gallows in the morning focusing the mind? It does.

At that point, I was pretty involved in the anti-war movement, and then an interesting opportunity came up. The 1971 May Day protests were being organized, and the goal was for people from all around the country to go to Washington, D.C., to block all the roads into town, to stop the government and stop the war — civil disobedience. With 200,000 others, I was off. I was arrested twice in the next four days, along with 14,000 of my brothers and sisters (the most arrests for any event in U.S. history).

It’s one thing to have an opinion. It’s another to act on it. For me, there were a few years of demonstrations. Demonstrations change you. Before I went to my first (protesting the firing of Clark Kerr, the University of California president, by the university regents upon the election of Ronald Reagan as governor), Steven Goodspeed, then dean of students at UCSB, made the following observation: The most affected people in a demonstration are the demonstrators. That is exactly true. And when you take the next step and go to jail, you cross another line. Now life is serious, and you get a sense of what is reasonable to do when push comes to shove. It’s a significant investment in your understanding of what citizenship means. I didn’t fully get that for a while (maybe a decade or so).

A role model for me back then was Dan Berrigan. He was the Jesuit chaplain at Cornell University when I was there for grad school. He spoke in poetry and of the moral alternative to war. He later served two years in federal prison for an exercise of conscience: using homemade napalm to burn draft files in the parking lot of a Maryland draft board.

A note here — during all these demonstrations, I had little hope of really changing anything. The mood of the country was not supportive of the counterculture and the anti-war movement. I was there because my schoolmates (and former football teammates) were getting killed. Sitting around listening to the Rolling Stones was just not on.

However, with the release of the Watergate tapes in 1974, it became clear that those demonstrations did have an effect on the occupants of the Oval Office. That was satisfying. It took another four years for the war to stop, but the point remains that really big, really bad things can change when we use the tools available in our democracy. Remember also the civil rights movement.

Also in those days, I saw many who dropped out of school. The ones who didn’t come back (that I know of) did interesting things. Most of my friends then were high-energy physicists.

One became an electrician, one a carpenter, one an investment banker, one a professor at Maharishi University and one a teacher. Many never came back. But the ones who did had new focus and much more realistic attitudes about school and career.

This leaves me with the following advice. At some break in your career — after high school, undergrad, grad — stop and get out of town. Do something really orthogonal with your life — Peace Corps or something in that line. Something where you have to leave the country and, importantly, do things for other people. Going to the developing world is a good choice. The point here is to find out who you are, what your natural gifts are. That’s a lifelong process, but this will be a big step in that direction, and at a critical time.

It’s also interesting who you meet when you’re on these journeys — other people doing just what you are (broadly) doing. It’s invigorating and supportive, and many will be friends for life. Some you may marry.

With your own eyes

In 2012, I accompanied my daughter on a trip to Haiti as part of a high-school project she and a friend had organized. My father had helped me similarly when I was 16. So I guess this was passing it forward.

My part in this exercise was to do a basic dental inspection of 300 beautiful children over the period of a week at an open-air church. There’s nothing I can tell you about what I saw that you haven’t heard many times on the news. But when you’re there and you’ve been a parent, it doesn’t take long before you begin to relate to those kids as your own. Parent genes are strong.

The majority had health issues. For a few, it was quite serious, but for most, $10 in medicine would take care of it. A Haitian doctor with us wrote the prescriptions, but it’s hard to imagine how any were filled.

I felt like, if I were 20 again, I would go to medical school so that I would have a practical skill to use in the world. We have enough scientists in the U.S. to handle all our biochemical needs. We don’t have enough physicians (and resources) to handle our world health needs. Seeing it with your own eyes changes everything. And that’s really the point of this whole discussion.

Courage

So, to students, I say maybe it’s time to stop and think a bit. Maybe it’s time for an internal sabbatical, and the more radical the course change the better. This advice may seem to be imprudent and impractical and to make little (or no) financial sense. But it works, and the only way to find that new trajectory is to step out of your comfort zone and, importantly, to get in touch with others doing the same thing.

After this journey, you may return to academics or a related effort as I did, refreshed and revitalized, or you may continue in a newly discovered passion as many of my friends have. Both are equally great.

It’s sort of the advice given in the last few paragraphs of a recent advertisement promising to make you a “Confident and Successful Industry Professional.” But realize that industry in many ways is not much of a change. There are lots of alternatives to consider. In contrast with the same advertisement, I would advise you not to overthink it. Go with your instincts. Or (if your instincts are not yet informed — which is likely) meet some interesting person and go with him or her.

Take action

The author went to Haiti in 2012 with his daughter. He recalls: “My part in this exercise was to do a basic dental inspection of 300 beautiful children over the period of a week at an open-air church. There’s nothing I can tell you about what I saw that you haven’t heard many times on the news. But when you’re there and you’ve been a parent, it doesn’t take long before you begin to relate to those kids as your own. Parent genes are strong.”Image courtesy of Hensley

The author went to Haiti in 2012 with his daughter. He recalls: “My part in this exercise was to do a basic dental inspection of 300 beautiful children over the period of a week at an open-air church. There’s nothing I can tell you about what I saw that you haven’t heard many times on the news. But when you’re there and you’ve been a parent, it doesn’t take long before you begin to relate to those kids as your own. Parent genes are strong.”Image courtesy of Hensley

These are very difficult times in the world. We need revolutionaries. So be one.

Forty percent of the world’s population doesn’t have potable water. From 2000 to 2003, 769,000 children under 5 years old in sub-Saharan Africa died each year from diarrheal diseases. Help change that.

A country’s access to medicines and treatments depends on a number of factors: efficient regulation, provision and use of products; and policies on selection, pricing and supply. It also depends on a qualified health workforce, information systems, functioning health infrastructure and good governance. There are a lot of opportunities here. Work with the World Health Organization and governments of relevant countries in one of those capacities to improve those conditions.

We have lived a very privileged life — handfed for all these years. We have an obligation to our fellows — who, by accident of birth, did not have this opportunity — not to waste this (our) opportunity. Again, a moral alternative to injustice and inequality.

This isn’t meant as national policy, of course, but personal suggestion. It may or may not work for you, but I’ll bet it does. Listen to about 10 TED talks and ask yourself, “Where did those people come from?” Very few come from career-development programs. One you might especially enjoy is by Zack Kopplin. As a high-school student, he organized 78 Nobel laureate scientists in a campaign against the Louisiana Science Education Act, a creationism law. It’s an example of what you can do even if the odds against you are great. (Kopplin won the Howard K. Schachman Public Service Award from the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in 2014).

But many, my wife among them, will say, “Wise up, hippie free spirit! These are not the ’60s. Students have crushing student debt. These are very different times. They are older and have families.” And that is the truth. So what to do?

First of all, regardless of time and circumstance, we all have responsibility for our lives. The bold experiment is always the best choice. It may take different forms depending on the times, but those choices are there.

One reasonable choice is one of the forms of national service that is available – Teach for America, AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps and so forth. These are redeeming programs, and many have student-loan repayment opportunities. And they will be life changing.

Student debt is the largest form of citizen debt in the country. If you were designing a country, would you put a $50,000 to $100,000 financial barrier to college entry in the way of the youth of your nation? Would you strap students with essentially a mortgage prior to their first day on the job? I’m not sure. If political activism is an option for you, what about pushing for a national plan to forgive student loans?

There are a lot of things that need help in our country. Probably at the top of the list is primary and secondary education. There are many opportunities there. Or one way to understand the issues around legislative reform in immigration is to work in an immigrant community for a few years. There are many opportunities there also.

I don’t mean to speak casually about the issues that our students and postdocs, or our nation, are facing. They are as serious as it gets, and it’s not a time to play. It’s your life (and maybe your family obligations) we’re talking about. But this can be a time to take stock of where we are as individuals and where we are as a nation and to make some courageous decisions.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Let’s make ASBMB awardees look more like BMB scientists

Think about nominating someone outside your immediate network.

A paleolithic peer review

You might think review panels have only been around for the last century or so. You would be mistaken.

Early COVID-19 research is riddled with poor methods and low-quality results

The pandemic worsened, but didn’t create, this problem for science.

So, you went to a conference. Now what?

Once you return to normal lab life, how can you make use of everything you learned?

My guitar companion

A scientist takes a musical journey through time and around the world.

Catalyzing change and redefining purpose

To mark Women’s History Month, Sudha Sharma writes about her journey from focusing on her own research program to being part of a collaborative COVID-19 project.