With a lot of help

from my friends

I originally had no intention of ever becoming a principal investigator. I just wanted to do my science and be left alone. Besides, I had no idea how one could as a woman; certainly there were few role models. But my boyfriend had different ideas: The way he saw it, I should get a job and support us, preferably somewhere on the West Coast.

As things turned out, I received an offer to become an assistant professor in the biochemistry and biophysics department at the University of California at San Francisco. At the time, UCSF was a little-known school, commonly referred to as the Medical Center. (Indeed, until her death, my mother maintained that I was a professor at UC-Berkeley.)

I arrived in San Francisco in the late summer of 1973 a nervous wreck. The department consisted of six other faculty, all male. They were very friendly and supportive (if a bit bemused to have a female in their midst). It was the postdocs who scared me: The women were desperate to have a Role Model and made clear their high expectations of me to give them advice, yet all I could serve up was my own insecurity.

It was slow-going setting up my lab, I received a negative midcareer review, and tragedy struck when my trusted mentor, Gordon Tomkins, died prematurely. I fell into a deep, clinical depression and was hospitalized for six long weeks. Remarkably, when my colleagues came to visit me, they each said, “I know exactly how you feel; this is a really hard job.” This was the first I had heard — or ever imagined — that anyone else was also feeling challenged, and the validation had an enormous impact.

Through a lucky series of connections, I became involved with a group therapy program whose belief was that emotional support and problem-solving skills were key ingredients to survival in a competitive environment. With the encouragement of the professionals leading this program, a group of friends and colleagues from various walks of academia initiated a leaderless group, in which we met to exchange experiences and offer advice in dealing with our usually shared problems. Thanks to this group, I ultimately was able to be granted tenure and to build a strong and nurturing lab environment. Now, some 35 years later, we still meet regularly every other Thursday (as Ellen Daniell suggests in her book of that name), and I am happy to take this opportunity to spread the word about this empowering strategy and encourage you to consider it to enrich your own lives.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

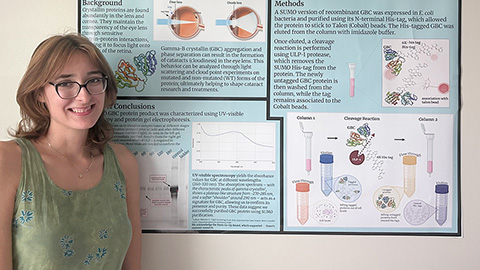

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.

How AlphaFold transformed my classroom into a research lab

A high school science teacher reflects on how AI-integrated technologies help her students ponder realistic research questions with hands-on learning.

Writing with AI turns chaos into clarity

Associate professor shares how generative AI, used as a creative whiteboard, helps scientists refine ideas, structure complexity and sharpen clarity — transforming the messy process of discovery into compelling science writing.